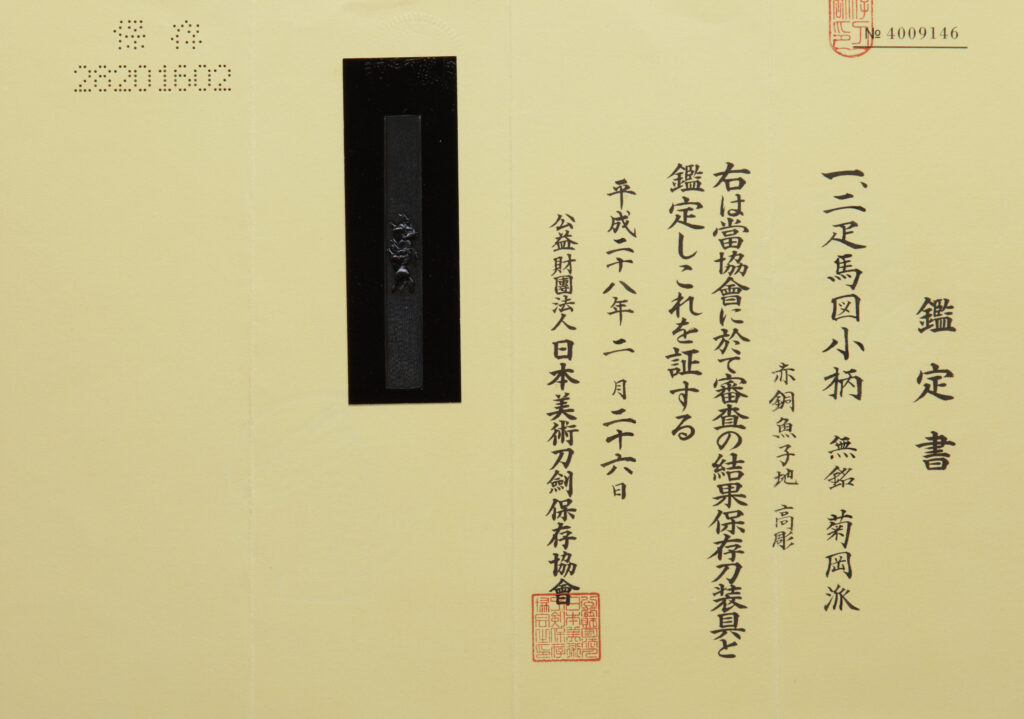

A Fine Kozuka from the Kikuoka School. REDUCED!

The emergence of the stylistically creative approach known as “machibori” or “town carving” was established by the Yokoya master, Somin. His training in the Goto tradition were the foundation of his skillset, but the constraints of the Goto tradition denied a larger creative expression. Somin sought to expand beyond convention and established a renaissance of tosogu design. The Machibori style thus stood in stark contrast to “Iebori” or “house carving” that refers to the traditions of the Goto and Yoshioka schools that catered to the Shogunate and other powerful families.

The Yokoya school in turn gave birth to subsequent schools such as the Yanagawa, founded by Yanagawa Naomasa that tuned their own styles and interpretations, while also harkening back to the origins of Machibori in fundamental and timeless themes such as Peonies and Shishi that emulated the Yokoya approaches. These creations were luxurious and exuberant thus attracting the mercantile classes, who were unconstrained to the mandates or dictations of tosogu design.

The Kikuoka school was founded by Mitsuyuki. He was born in 1750 to a culturally educated family of haiku and waka poets, and continued in this profession while also studying metalwork with Yanagawa Naomitsu. Mitsuyuki’s grandfather was named To’emon Fusayuki and originally hailed from Iga province before moving to Edo sometime in the Genroku era (1688-1704). He took the Poet name of Senyro establishing the first generation of this name that his grandson, Mitsuyuki, would later assume as the third generation. Mitsuyuki died in October of 1800 at the young age of 51.

Records reflect on the fact that the Kikuoka family was plagued by premature deaths of its members. Mitsuyuki was had succeeded as head of the family eventhough he was not the first born. Mitsuyuki’s son, Mitsutomo would become the 2nd generation head of the school in 1799, just prior to Mitsuyuki’s death and since Mitsuyuki was quite young when he died in October of 1800 at the age of 51, it could be speculated that Mitsuyuki’s death was anticipated. Mitsutomo had taken the head of the school because his older brother, Hideyuki, had already died at the age of 21. Mitsutomo himself died in April of 1813 at the age of 38, less than 13 short years after his father, leaving reconciliation of the problem of succession to Mitsuyuki’s younger brother, Samonji Mitsumasa. Mitsumasa and the other members of the Kikuoka school decided that Mitsushige would assume the 3rd generation leadership of the school.

Around all these unfortunate deaths within the Kikuoka school, Mitsumasa clearly stood out as the anchor that held the school in place during turbulent times. Mitsumasa was Mitsuyuki’s younger brother and had supported Mitsuyuki when he decided to become a metalworker after studying with Yanagawa Naomitsu. Mitsumasa also assumed care for Mitsutomo and Mitsushige after the death of his older brother, thus ensuring the continuation of the school. It is interesting that Mitsumasa, though clearly a highly skilled artist as seen from his many extant works, did not assume the helm of the school. The directives of Mitsuyuki would thus appear to have been quite clear on the subject of succession, and proves the loyalty and dedication Mitsumasa held for his older brother.

The workmanship of the Kikuoka school can accurately be described as poetry in sculpture. The poetic influence is manifestly illustrated by lively, exuberant, and intricate design work that explored the width and breadth of the machibori freedom of aesthetic. The usage of the highest quality materials is also evident, such as the deep lustrous blue-black shakudo, also shows their uncompromising commitment to excellence.

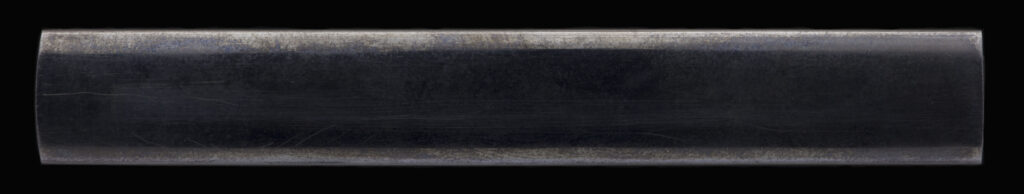

This kozuka is constructed of high quality shakudo alloy. The horses are sculpted in a charming and playful manner, and set on top of superbly rendered nanako background. The skill that is required to create such consistently accurate nanako is a basis point for the overall caliber of a school or maker’s work as it is rudimentary.

Nanako is created using a hammer and a single “dot” punch, one by one at a time. If the pattern is to be unified to create a sort of “veil”, they must be placed perfectly, and punched equally in strike so as not to have any disruptions. The slightest inconsistencies will cause a loss to the desired outcome of a pattern of individual beads that disappears into itself becoming a uniform texture.

This piece is unsigned but is attributed directly to the Kikuoka School by the NBTHK with a Hozon Tosogu paper. It is a wonderfully crafted kozuka that is exemplary of the skill and dedication of the Kikuoka craftsman and would be a fine addition to any collection.

On Consignment: REDUCED! Now $2950.00 USD